In this issue we:

- Describe key inflammatory and fibrotic mechanisms in IgA nephropathy

- Share preclinical data from studies with sparsentan in mouse and rat models showing anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects independent of blood pressure reduction

- Explain the role of key urinary biomarkers in reflecting kidney-localized inflammation and fibrosis and understand their potential application to clinical studies

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) and angiotensin II (Ang II) perpetuate a cycle of injury in IgA nephropathy, contributing to renal inflammation and fibrosis1

IgA nephropathy is the most common form of primary glomerulonephritis and is caused by the deposition of IgA in the glomerular mesangium.2,3 This deposition triggers local inflammation and fibrotic remodeling that can lead to kidney damage, nephron loss, and progression to kidney failure.1

ET-1 and Ang II are key mediators of disease progression.1 Both have similar pathophysiological roles and together contribute to hypertension, glomerulosclerosis, and proteinuria, in addition to inflammation and fibrosis.1,4,5

Figure. The roles of ET-1 and Ang II in the kidney5

Renal inflammation occurs when ET-1 and Ang II stimulate the release of inflammatory signals, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor (TNF).5-8 These signals drive inflammation and trigger fibrosis by activating transcription growth factor-β (TGF-β), leading to fibroblast activation and matrix buildup.9,10

Simultaneously, ET-1 and Ang II also induce oxidative stress, promoting upregulation of genes involved in fibrosis, inflammation, and tissue remodeling, further amplifying kidney damage over time.5,9,11-13

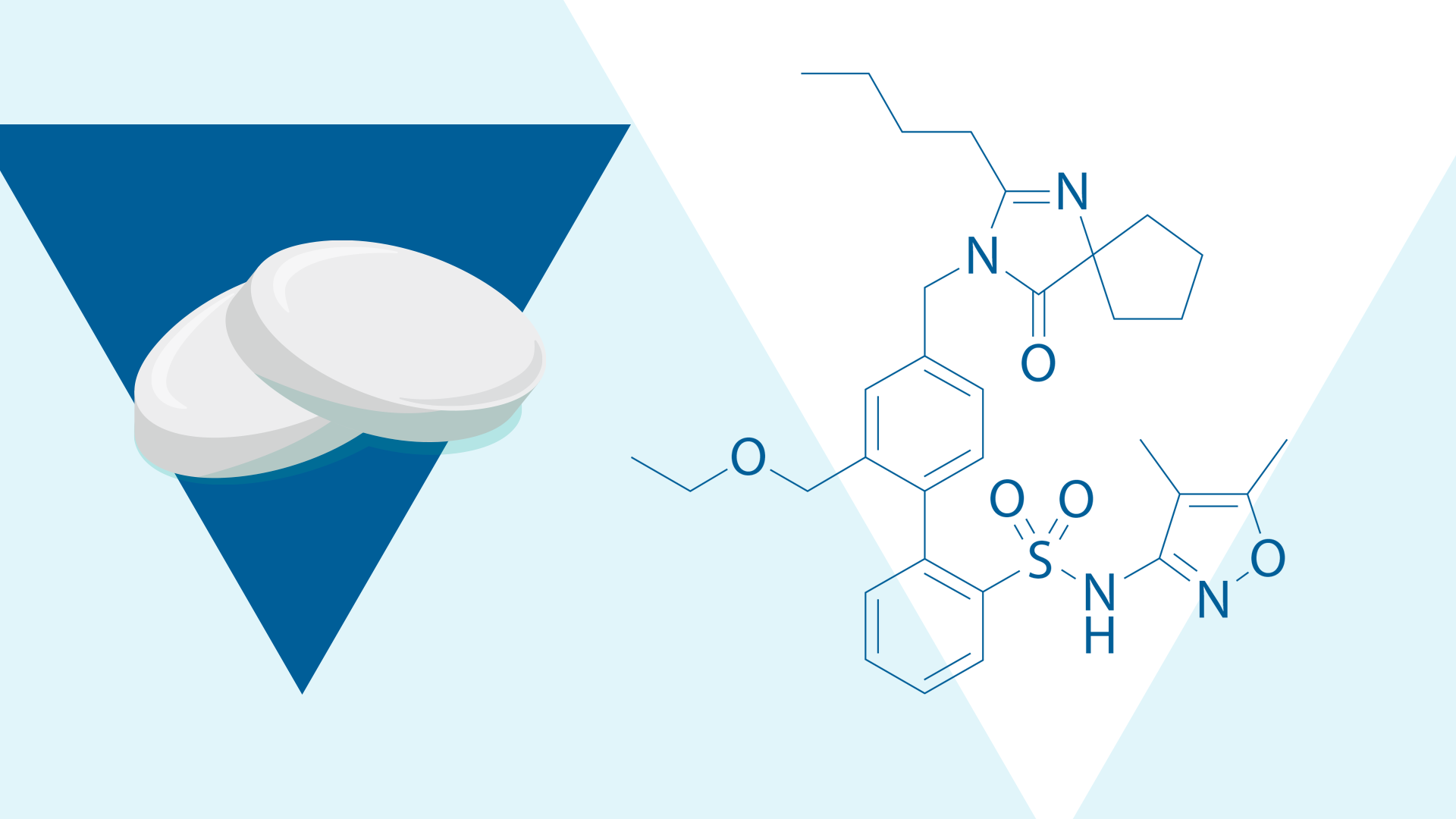

Sparsentan has demonstrated anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory effects in preclinical studies1,12,14,15

In IgA nephropathy, sparsentan protects the glomerulus by simultaneously blocking the activity of ET-1 and Ang II.1 To evaluate its intrarenal effects, several animal models mimicking key features of IgA nephropathy were used, including the gddY mouse, the IgA1-IgG engineered immune complex (EIC) mouse, and the anti-Thy1 rat.12,14,15 These models reproduce hallmark features of the disease such as mesangial proliferation, inflammation, and fibrosis.12,14,15

Across models, sparsentan consistently showed anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic activity.12,14,15 In the EIC and gddY mouse models, sparsentan ameliorated expression of inflammatory, immune response, and proliferative gene pathways.12,14 In the EIC model specifically, sparsentan also attenuated gene expression of C1q components of the classical complement pathway.12 In the anti-Thy1 rat model, sparsentan led to dose-dependent reductions in glomerular macrophage infiltration.15

Figure. Impact of sparsentan on expression of immune and pro-inflammatory signaling in kidneys of gddY mice

Collectively, preclinical findings indicate that sparsentan targets immune and inflammatory processes leading to protection from mesangial hypercellularity.12,14,15 Notably, reductions in urinary biomarkers observed in the Phase 2 open-label SPARTAN study may reflect the translation of these preclinical findings into a clinical setting.16

In addition to reducing inflammatory activity, sparsentan has demonstrated anti-fibrotic effects in preclinical models of IgA nephropathy.14,15 In the anti-Thy1 rat model, treatment with sparsentan led to dose-dependent attenuations in interstitial myofibroblast activation.15 Similarly, in the gddY mouse model, sparsentan ameliorated the increase in mRNA expression of genes associated with profibrotic signaling pathways.14

These molecular changes were accompanied by improvements in histological markers of kidney injury across both models.14,15

Figure. Impact of sparsentan on models of renal fibrosis

Urinary biomarkers may one day provide insight into renal inflammation and fibrosis without the need for repetitive kidney biopsies17

While kidney biopsy remains the gold standard for assessing inflammation and fibrosis in IgA nephropathy, its invasive nature limits its use for ongoing disease monitoring.18 Today, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and proteinuria are the only validated biomarkers in clinical practice for IgA nephropathy.18 However, studies are increasingly investigating urinary biomarkers for noninvasive disease evaluation.16

Several interconnected urinary biomarkers have emerged as potential indicators of inflammation, immune activation, and fibrotic remodeling in IgA nephropathy.16

Figure. Network map of urinary biomarkers16

While not yet used in clinical decision-making, these biomarkers may provide insight into kidney-specific disease activity in ongoing studies.16,17,19-23 In clinical studies, including the Phase 2 SPARTAN and Phase 3 TESTING trials, these biomarkers have been used to explore underlying inflammation, fibrosis, and kidney injury.16,24

Figure. Urinary biomarkers in IgA nephropathy

Collectively, these biomarkers offer a dynamic snapshot of renal pathology, supporting the long-term goal of monitoring disease progression without the need for repeat biopsy.16,17,19-23

Exploring the Mechanism of Sparsentan in IgAN: Including a Spotlight on Urinary sCD163, a Key Marker of Inflammation

Learn how u-sCD163 is being used to assess kidney specific inflammation in the SPARTAN study

Stay tuned for the next issue to learn how urinary biomarkers are being used to evaluate anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic treatment effects of sparsentan in IgA nephropathy in the Phase 2 open-label SPARTAN clinical trial.

Related Content

Targeting Inflammation and Fibrosis in IgA Nephropathy: Insights from the Phase 2 SPARTAN Study

Learn about clinical and biomarker findings from the Phase 2 SPARTAN trial in IgAN

Exploring the Mechanism of Sparsentan in IgAN: Including a Spotlight on Urinary sCD163, a Key Marker of Inflammation

Learn more about the role of u-sCD163 in IgAN and the biomarker findings from the SPARTAN interim analysis!

Footnotes

- Kohan DE et al. Clin Sci (Lond). 2024;138(11):645-662.

- Pitcher D et al. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;18(6):727-738.

- Wyatt RJ et al. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(25):2402-2414.

- Rüster C et al. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(7):1189-1199.

- Komers R et al. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2016;310(10):R877-R884.

- Dhaun N et al. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167(4):720-731.

- Maranduca MA et al. Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(4):3541-3545.

- Leonard M et al. Kidney International. 1999;56(4):1366-1377.

- Trimarchi H et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34(8):1280-1285.

- Boyd JK et al. Kidney Int. 2012;81(9):833-843.

- Arendshorst WJ et al. Antioxidants (Basel). 2024;13(12).

- Reily C et al. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2024;326(5):F862-F875.

- Xu Y et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2025;gfaf209.

- Nagasawa H et al. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2024;39(9):1494-1503.

- Jenkinson C et al. Presentation at: International Symposium on IgA Nephropathy; September 27-29, 2018; Buenos Aires, Argentina.

- Cheung CK et al. Presented at: International Podocyte Conference & ISGD Meeting, 2025; June 10-13, 2025; Hamburg, Germany. FR_11.

- Xu Z et al. Clinical Immunology. 2025;274:110468.

- KDIGO 2025 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Immunoglobulin A Nephropathy (IgAN) and Immunoglobulin A Vasculitis (IgAV). Accessed 30 October 2025. https://kdigo.org/wpcontent/uploads/2024/08/KDIGO-2025-IgAN-IgAV-Guideline.pdf.

- Keskinis C et al. Medicina (Kaunas). 2025;61(5).

- Chen L et al. MedComm (2020). 2024;5(11):e783.

- Luo R et al. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8(6):381.

- De Cos M et al. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2024;84(2):205-214.e201.

- Lu Z et al. Frontiers in Medicine. 2025;12.

- Li J et al. Kidney International Reports. 2024;9(10):3016-3026.

- Cheung CK et al. Front Nephrol. 2023;3:1346769.

- Yu BC et al. J Clin Med. 2022;11(3).

- Zhao W et al. Kidney Int Rep. 2023;8(3):519-530.

MA-SP-25-0132 | November 2025